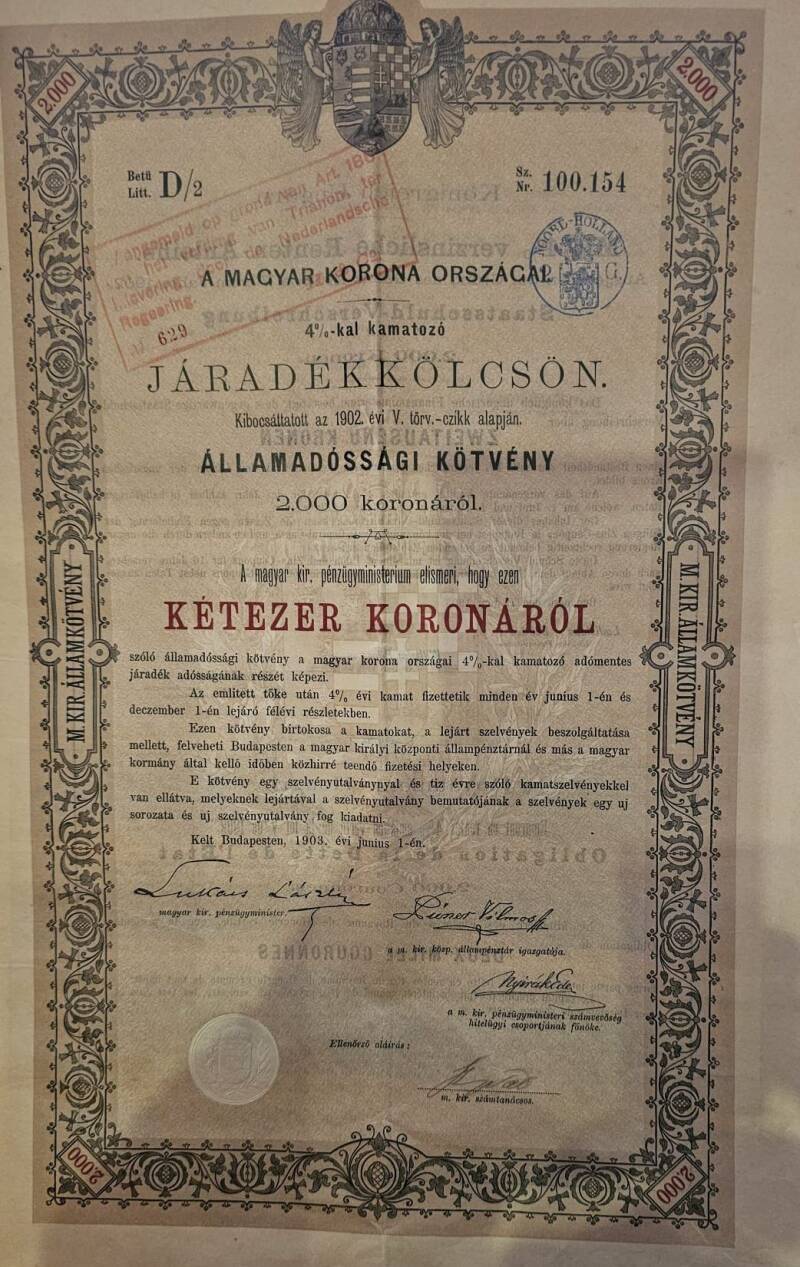

The document in question is a Hungarian government bond ("államadóssági kötvény") issued by the Kingdom of Hungary in 1903. It was released under the provisions of the 1902 V. law article and had a nominal value of 2,000 Korona. The bond carried an annual interest rate of 4%, reflecting the financial instruments and economic stability typical of the Austro-Hungarian Empire during that era.

In terms of historical purchasing power, 2,000 Korona in 1903 represented a significant sum. It would have been equivalent to several years' wages for an average worker, indicating that the bond was likely aimed at wealthier individuals or institutions rather than the general populace. It served both as a savings tool and as a government debt instrument, promising steady returns through its annual interest payments.

The value of the Korona underwent major changes in the subsequent decades. Following World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated, leading to severe economic instability. The Korona suffered rapid devaluation and hyperinflation between 1919 and 1927. Ultimately, in 1927, Hungary replaced the Korona with the Pengő at a conversion rate of 12,500 Korona to 1 Pengő. This transformation rendered old Korona-based assets, including bonds like this, essentially worthless in official financial terms.

Further compounding the loss, Hungary experienced one of the most extreme cases of hyperinflation in world history after World War II. The Pengő collapsed in 1946, necessitating the introduction of the Forint as the new national currency, at an astronomical conversion rate of 400,000 quadrillion Pengő to 1 Forint. As a result, any previous monetary instruments tied to the Korona or Pengő were effectively nullified without compensation, making the original bond's face value legally void.

Today, however, such historical financial documents are prized by collectors and historians. In the field of scripophily—the study and collection of old bonds and share certificates—Hungarian government bonds from the early 20th century can fetch between 50 and 200 EUR, depending on factors such as condition, rarity, and presentation. Particularly well-preserved examples, possibly framed or accompanied by additional documentation, can even achieve prices exceeding 300 EUR at specialized auctions.

Further compounding the loss, Hungary experienced one of the most extreme cases of hyperinflation in world history after World War II. The Pengő collapsed in 1946, necessitating the introduction of the Forint as the new national currency, at an astronomical conversion rate of 400,000 quadrillion Pengő to 1 Forint. As a result, any previous monetary instruments tied to the Korona or Pengő were effectively nullified without compensation, making the original bond's face value legally void.

Today, however, such historical financial documents are prized by collectors and historians. In the field of scripophily—the study and collection of old bonds and share certificates—Hungarian government bonds from the early 20th century can fetch between 50 and 200 EUR, depending on factors such as condition, rarity, and presentation. Particularly well-preserved examples, possibly framed or accompanied by additional documentation, can even achieve prices exceeding 300 EUR at specialized auctions.

For those curious about the hypothetical, it is interesting to consider what the bond’s value would be today if its purchasing power had been preserved. In the early 1900s, 1 Korona was approximately equivalent to 0.5 grams of gold, owing to the then-prevailing gold standard. Therefore, 2,000 Korona would correspond to roughly 1 kilogram of gold. With gold prices around 65,000 EUR per kilogram as of April 2025, the bond’s implied value in today’s gold terms would be approximately 65,000 EUR. This figure highlights the enormous erosion of real value suffered by holders of historical paper assets during periods of political and economic turmoil.

Finally, if we were to imagine the original 2,000 Korona reinvested continuously at a 4% annual interest rate for the past 122 years, the compounded returns would produce an astronomical figure. Although purely theoretical, this exercise underlines the tremendous potential of compounded growth—and the destructive impact that political and monetary instability can have on even the soundest financial plans.

Add comment

Comments